.

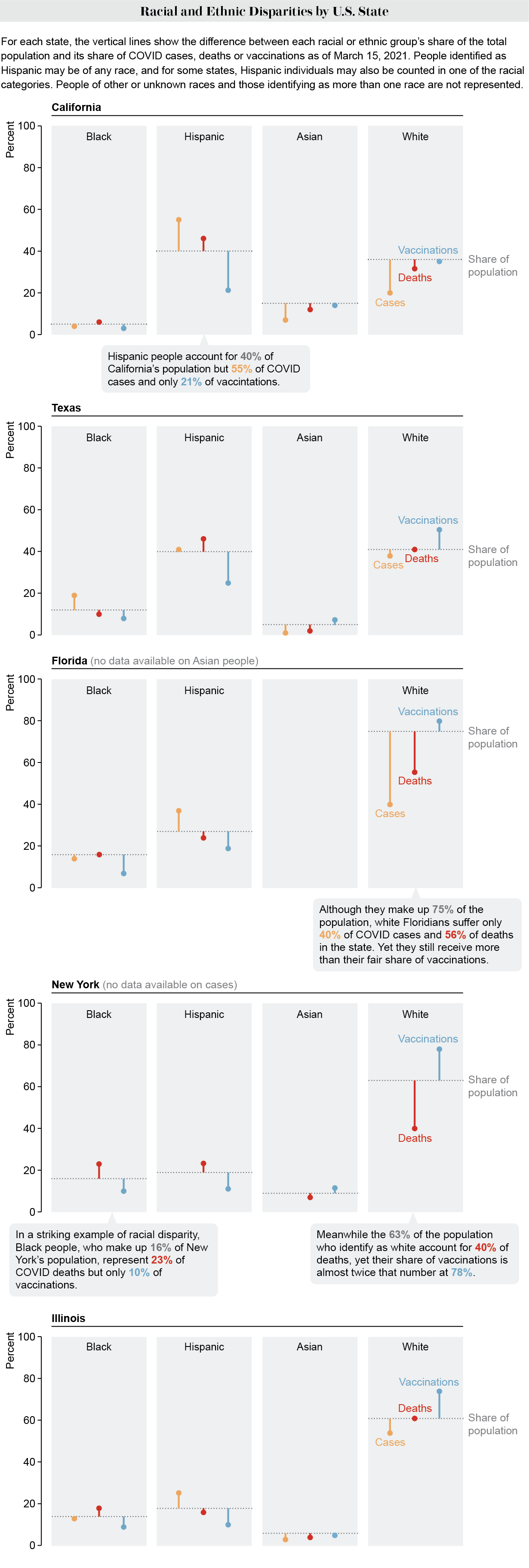

Stories of such inordinate hurdles are relatively common and may assist describe why Hispanic and Black individuals in lots of states are getting vaccinated at disproportionately lower rates than white or Asian people– in spite of having a greater problem of COVID-related death and disease. The Kaiser Family Foundation gathers data onCOVID cases, deaths and vaccination rates among individuals who determine as Black, white, Asian or Hispanic. Scientific American visualized these information for five populous states with a few of the worst COVID outbreaks: California, Texas, Florida, New York City and Illinois. The graphic below shows that Hispanic people had a few of the most affordable vaccination rates proportional to their share of the population, particularly in California and Texas. Black individuals in New York, Illinois and Florida are getting immunized at significantly lower levels.

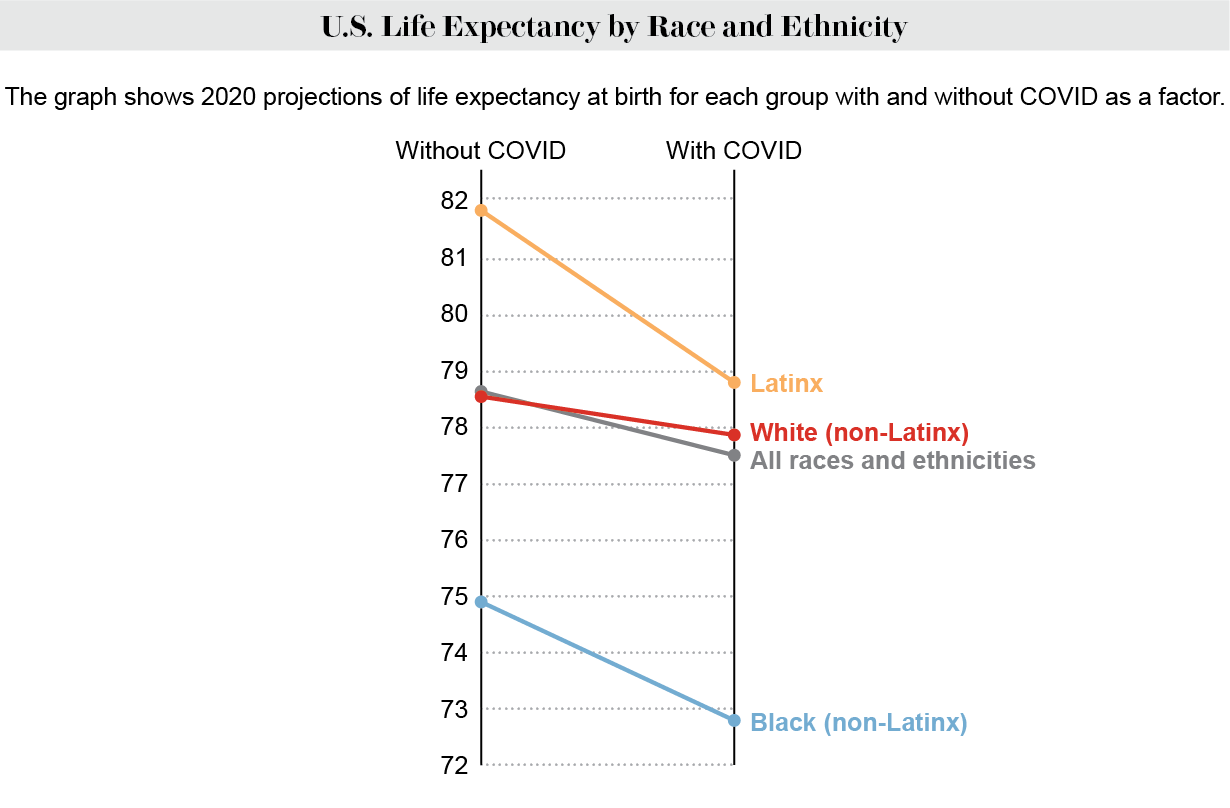

Numerous aspects may be behind these inconsistencies [see additional graphics]: Age minimums for COVID vaccination might favor white Americans, who have a longer life span than Black Americans.

One of the primary qualifications for a COVID vaccine in many states is being older (normally age 60 or above), which is known to be amongst the most significant threat factors for serious disease and death from the novel coronavirus. Since of Black Americans’ much shorter life span, fewer of them may be eligible for a vaccine– in spite of being at a higher danger of death than similar-aged or older white individuals.

Twin physicians Oni and Uché Blackstock discussed this variation in a recent Washington Post op-ed calling for lower age limits for Black people to get vaccinated. “These age cutoffs disregard the effect of systemic bigotry on reducing Black Americans’ lives,” Uché Blackstock, founder and CEO of the company Advancing Health Equity, told Scientific American “Ignoring the reality that we have actually had Black Americans of more youthful ages pass away at greater rates than white Americans– even 10 years older than them– I believe reinforces these inequities.”

Interestingly, Hispanic individuals in the U.S. have a greater total life span than non-Hispanic white individuals, in spite of generally having a lower socioeconomic status. This has actually been called the “Hispanic paradox,” or “Latino paradox.” Possible explanations include the “healthy immigrant effect”– the truth that current immigrants tend to be much healthier than the in your area born population– along with behavioral elements such as diet plan and lifestyle. Latinx people have likewise had the greatest drop in life span because of COVID, so it does not make sense to raise the age cutoff for vaccination in that group.

” Right now the most important barrier is genuinely the limitation around age just and not allowing for race to be sculpted out as its own classification,” says Nneka Sederstrom, primary health equity officer at Hennepin Healthcare in Minnesota.

The problem originates from “a deep-rooted inability to name race as its own aspect” in illness risk, Sederstrom states. She includes that every attorney she has sought advice from competes that singling out race as a criterion for eligibility violates the 14 th Modification, which extended citizenship and equivalent rights to Black Americans and anyone born or naturalized in the U.S. “If you’re stating that the change that gives us the chance to allegedly deal with equity and equality is the important things that’s in the way of in fact dealing with equity and equality,” Sederstrom states, “then we require to change that.”

Some areas have actually already had the ability to use lower age cutoffs for immunizing Native Americans, who have actually likewise ended up being sickened and died at greater rates during the pandemic.

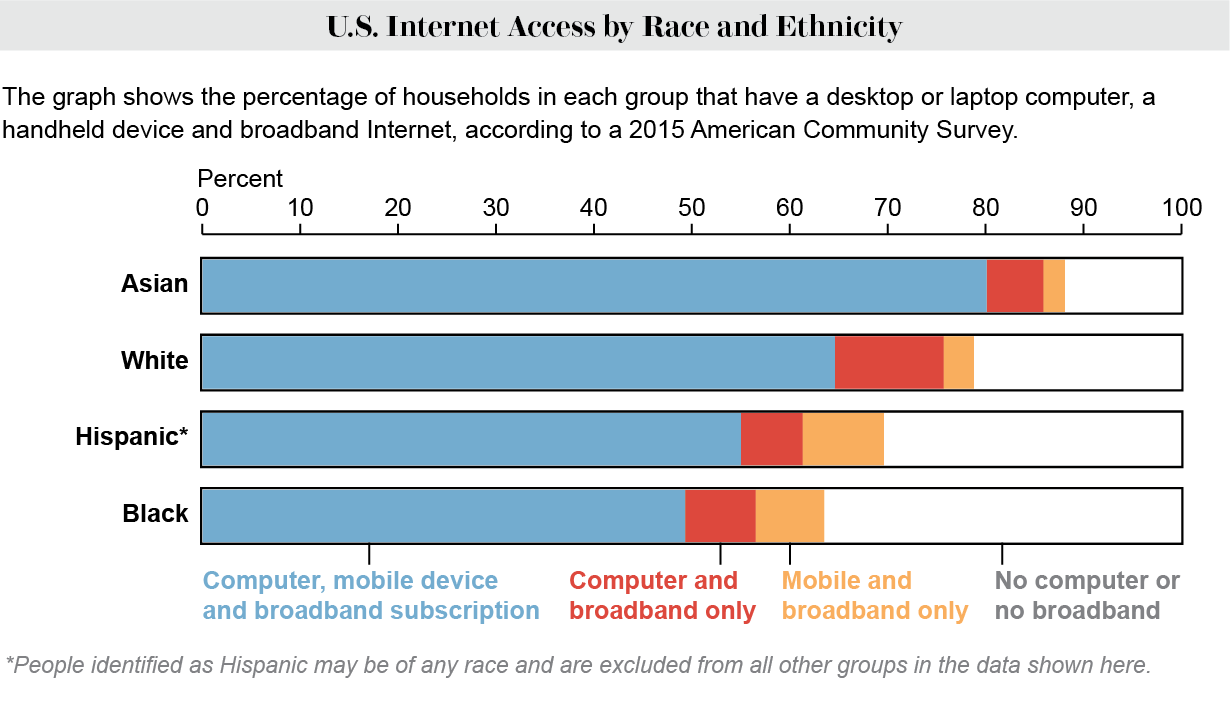

Another barrier to getting vaccinated is trouble in signing up for appointments online. Applicants frequently need to navigate labyrinthine portal systems and submit multiple pages of documentation before consultations fill, so it ends up being a race for who can pack and complete the forms the fastest. A 2015 survey found that a smaller sized percentage of Black and Latinx families have computer system and broadband gain access to than white and Asian households. And many individuals of color operate in per hour jobs that do not provide time off to spend long stretches of time searching for vaccine appointments.

In Maryland, the Vaccine Hunters have actually been helping elders and individuals of color register for visits. “It ended up being a video game of ‘How quick can you type?'” states Maria Peterson, a member of the group. “It resembles The Cravings Games“

One issue for Hispanic individuals has been Web sites with bad Spanish translations– frequently resulting from a typical automated tool. “The grammatical errors we discovered would have made it impossible for a Spanish speaker to figure out what was being asked,” says Peterson, a native Spanish speaker who teaches the language at the high school level.

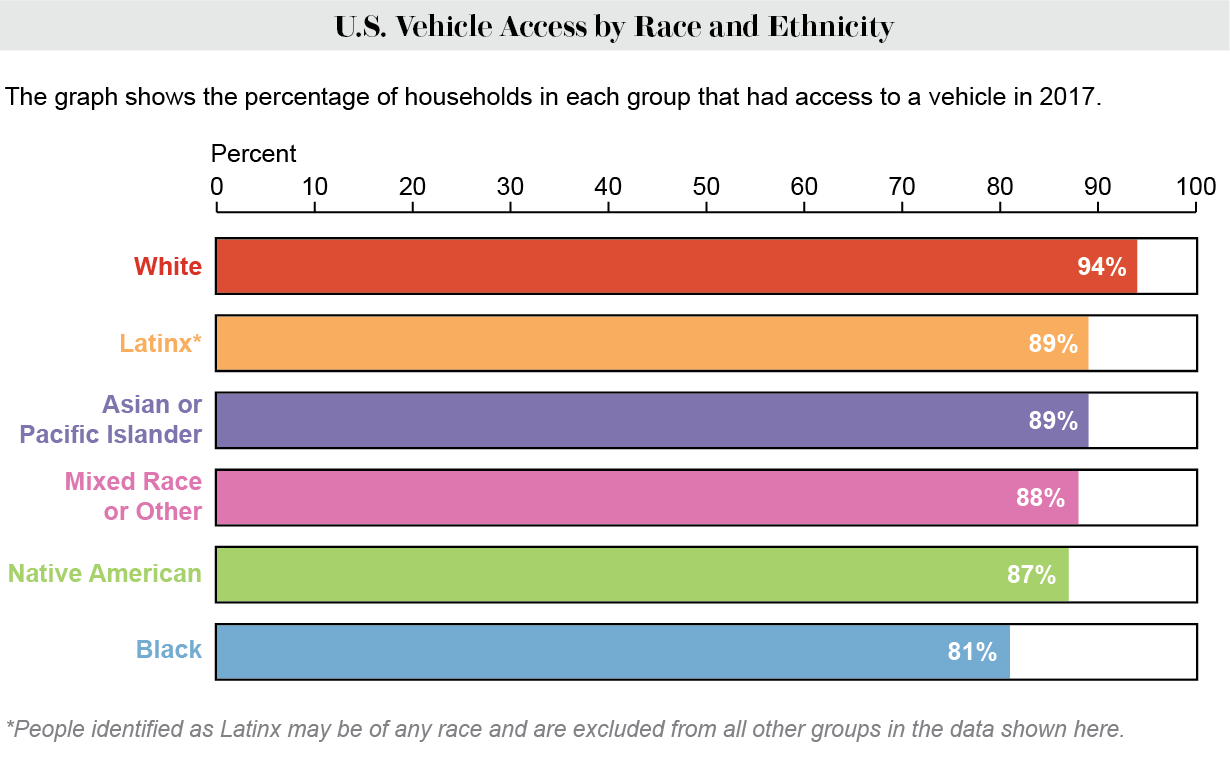

Getting to vaccination sites can also be a challenge. They are not always near public transit, and not everyone has access to a vehicle. An analysis of survey data discovered that in 2017 Black homes were the least likely of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. to own an automobile, followed by Native American households. Montgomery is Maryland’s many densely inhabited county, with a great city system and buses. Its closest mass vaccination website is at a 6 Flags America style park, which is a several-hour bus ride from the majority of parts of the county.

In Chicago’s South Side, which is primarily Black, one should make a 30- minute drive or take a roughly hour-long bus ride to get to the mass vaccination website at the United Center in the city’s downtown area, says Armani Nightengale, a contact tracer at the Calumet Location Industrial Commission who is also helping individuals make vaccination appointments. “We had an instance of visits opening the day of, and we asked people if they wanted to be available in today,” Nightengale says. “One girl was like, ‘Are you joke me? How am I going to get there?'” Many individuals have work or are looking after children and can not just drop everything to get immunized. Taking public transit presents a prospective COVID exposure danger, and ride-sharing is costly, she includes.

In addition to these barriers, there is the concern of vaccine hesitancy. Black Americans are still more likely than white Americans to withstand getting a vaccine, although this space has decreased with time

Uché Blackstock thinks a number of the issues people have about vaccination are addressable. “A lot of people of color who have issues about the vaccine are not a determined ‘no,'” she states. “A substantial percentage are ‘wait and see.'”

” Hesitancy does not mean refusal,” Sederstrom notes.

Editor’s Note: The term Hispanic refers to individuals of any race whose heritage is in Spanish-speaking countries.

No comments:

Post a Comment